A Manufactured Object of Devotion

Faith in an age of devastation.

In the event of imminent nuclear attack1, the religious sensibility above all else is subjected to severe strictures. It may break under those strictures in three ways.

First is through hyper-piety, when pre-existing religious belief is provoked by the threat of mass annihilation into an acute level of devotion always assumed but never seen under conventional conditions. Preparation for survival is set aside in favor of preparation for the End, consisting of a cycle of confession, atonement, and prayer to assure safe passage beyond the temporal plane.

Second is through sudden piety. This is belief induced by panic, after long-present rational faculties prove futile against events that defy all logic and open the rational to reconsider irrational positions. As such, the preparations above mentioned are adopted in haste and undertaken clumsily with little distinction between cycles. More immediate practical matters, too overwhelming to contemplate, are at best partially completed. Their exit from the temporal plane is every bit as certain as that of the hyper-pious while their destination thereafter is more ambiguous.

And third is through extreme impiety, for whom the revelation of absolute destruction only proves the Godlessness of the universe. This type breaks down into two smaller categories. Some are ultra-utilitarian, securing to the utmost of their passion their material survival. Others, however, are fatalistic, preferring to dispense with unnecessary expending of energy and to let the void come to them. If actual survival rates are higher than the first two types they are so only by slight degrees.

These three types enjoy a wide acceptance and are anticipated in the survival schemas of most civilized states. But a little-appreciated fourth type must be considered if these schemas aim for completeness. Consider it a kind of fusion of the three, or really a mutation as it resembles but does not copy them. It is also the least consciously adopted of them, being guided more directly by conditions. It is better described than named.

An ICBM is fast approaching you and your loved ones. You are secular and remain so under duress. Nor do you succumb to extreme utilitarianism or fatalism. You accept what is happening soberly. You carry out your tasks with cool deliberation. You consult the survival guide with care, you overlook no steps and ignore no outcomes. And lo, it works. You and your loved ones have built an adequate shelter and can endure the hazards of fallout and the other atmospheric disruptions.

When you emerge, all is changed. The other three types are dead or otherwise incapacitated. The world you shared, to say nothing of the attitudes they brought to it, is dead with them. You are burdened with having to forge ahead into the extreme of uncertainty. But you do so with significant realizations. That process of preparation, for one thing, filled you with a purpose wholly absent in your life before the attack. A truth of cosmic import revealed itself to you, and you responded with what in hindsight has all the makings of ritual. Like the Desert Fathers that you’ve sort of heard about, your shelter was actually a monastic cell, in which you retreated from a fallen world, fasted, and contemplated. When needed you observed new burial rites and new mourning practices. You understood your body and the bodies of others in unexpectedly vulnerable and intimate ways. You exited your cloister not just as a survivor but as a new spiritual presence. The burden is also a blessing, but one that must be undertaken with still greater care.

You will find that other survivors pulled through with the same mindset. You are equal with each other in coming to terms with the apocalypse. This is made easier by coming together under a unifying consensus, which with time should prosper into a coherent belief. It is important to establish this quickly. This consensus, as we shall find out, is precarious. You all know the following: (1) something greater than yourselves is necessary to offer some sort of balance and (2) the only available object is the very thing you all survived.

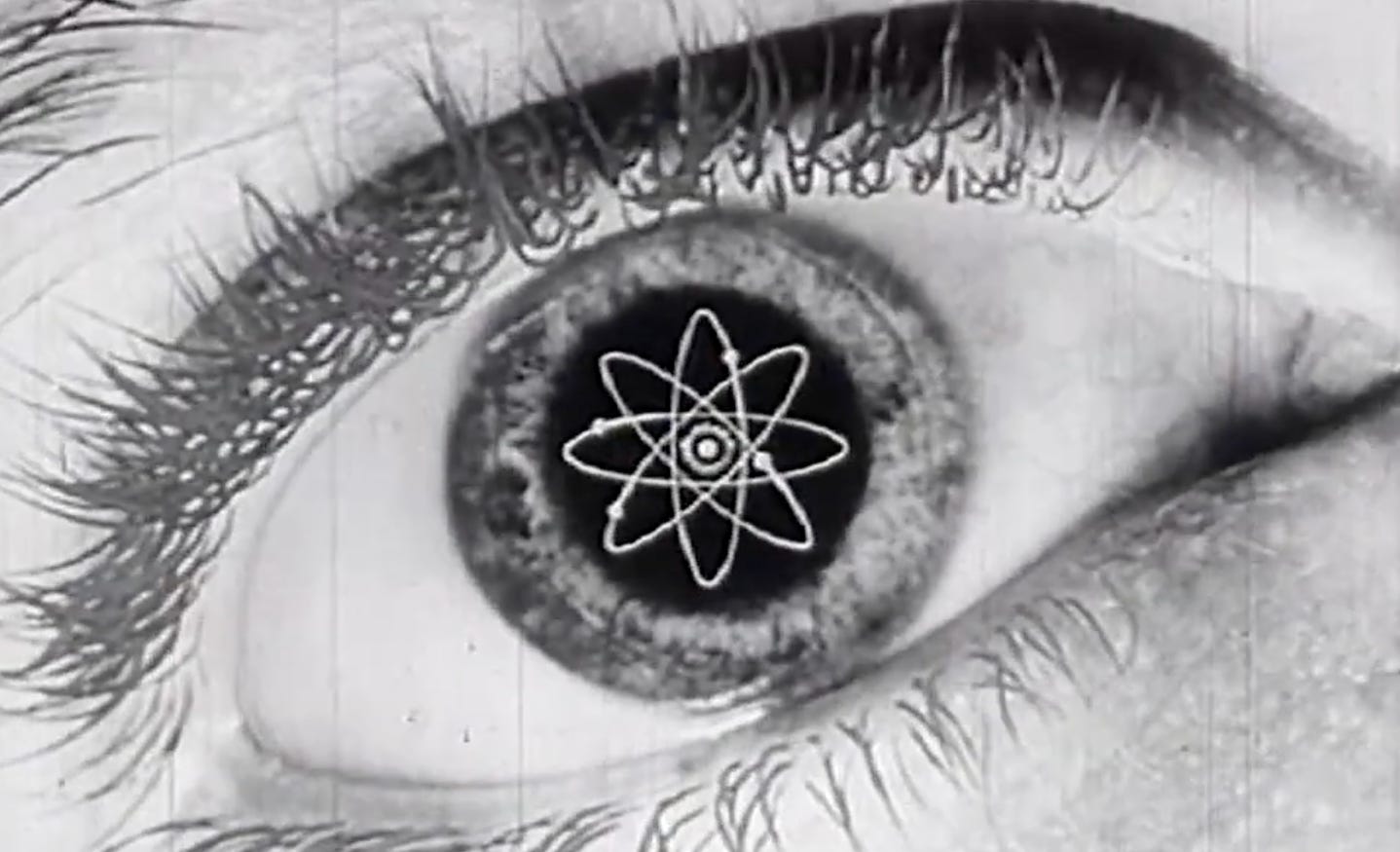

Destructive times often correspond with destructive deities. “The Bomb” earns this status first by the sheer scope of its awe. Even before detonation it demands respect. Its hammerhead shape is as much a display of its brutality as it is a necessity of scientific design. It’s honest. It contains no more knowledge than is required by its purpose: the delivery of a simple but very concrete message. And second by our intimate connection with it as its authors and guardians. It serves as an ideal of our self-image. Americans cherish simplicity and honesty even if they themselves are often complicated and dishonest. In other words, the bomb is a better version of us. The bomb is at the center of man’s conscience. It embodies man’s character and exerts total control over his life. Once something establishes dominance it is impossible to disobey and very difficult, not to mention unwise, to openly profane. Such is where you find yourself in the present context.

When articulating a religion for a post-fallout context, it helps to understand first what is absent. You may have had some familiarity with certain accoutrements long taken for granted in a civilized age: grace, mercy, and the cosmos as a spiritual adhesive that bound you to the divine. While they may persist in some residual sense on an individual basis, you are likely to find no vocal adherents to them among the community of fellow survivors. A new religion, like a new shelter, must be built and built with what little resources remain after the collapse. Thankfully even a cursory survey of your surroundings will indicate exactly what is required for this endeavor.

The consensus you’d achieved with the other survivors begins to show signs of breakdown. As memory of the religious amenities fade, so too does memory of their civil counterparts. Through a potent cocktail of negative emotions, people find themselves more willing than usual to detach their consciences from customs of shared bodily autonomy and personal freedom more generally. Indeed, whole notions of what it means to be a “person,” long thought fairly coherent and solid, dissolve into a kind of mist. Having seen your loved ones succumb to these changes in one way or another, and having felt their pangs within yourself, you know that the will to resistance is necessary but not sufficient on its own. You require a moral framework, enforced by concrete and applicable dogmatic principles, and overseen by a single figure of infallible authority, for which the bomb, or its specter, possesses the most persuasive force.

The challenge is that the bomb derives its force by its awesome silence, leaving you as its interpretive voice. As far as you can tell, the devastation of the bomb is less the consequence of a war than the imposition of a test. A test that is meant to prove the immutability of the human character. The collapse of consensus splits the survivors into two camps. You count yourself among the atomic faithful. The others, for lack of a better term, are the atomic heathens. The heathens lacked the strength to withstand the temptations of your new world and so take every effort to assume an animal existence. Where previous religious sentiment operated on the redemptive potential of all, this, too, is incompatible with the present context. The heathen are beyond repair, yet at the same time they serve as a cautionary example of the impossibility of total transformation. Animals, having no access to reason, rely on raw instinct and nothing else. Humans seeking to live by that same animal instinct merely reason themselves into a deteriorated state of reason.

As the bomb has demonstrated, you can either refine against new circumstances or degrade. You and your fellow faithful have chosen the path of refinement. You base your entire lives partly celebrating that refinement and partly working to maintain its integrity. From this new rituals are formed and practiced. None have any resemblance to rituals as understood in stabler times. The antebellum version of yourself will have found even the suggestion of these rituals beyond good taste. They present as, to use the polite term, “momentary lapses of judgment.” But the bomb demands nothing less. By your command, the atomic faithful lash themselves before its point of detonation. They make “peace offerings” on the anniversary of its revelation so as to forfend a second one. For the fear of the bomb is as potent as its power. A well-grounded fear at that. As the offending country, being hypersensitive to that protection gained by its decision for its continued civilizational niceties, may see fit to deploy an additional round of missiles.

The term “peace offering” carries here a special significance. “Peace” has always been a religious watchword. But in the antebellum period its definition was often muddled where it wasn’t just meaningless. Worse, peace found itself conflated with freedom as an equal and as being mutually inclusive. You in the postbellum context, however, are the keeper and benefactor of a new and more precise definition of peace. On the surface it is the stillness in the aftermath of devastation, yet further below it is the apprehensive respite from the looming threat of freedom as expressed by the pseudo-animals in your midst.

So vast is your comprehension of peace that it comes to eclipse still more once-cherished concepts of faith. Add to mercy, grace, and redemption also love, hope, charity, and justice. You cling to and jealously guard peace, knowing that the slightest neglect will cause it to fall away, and for which vengeance is the only viable successor. And vengeance, unlike peace, never needs upkeep or vigilance. Vengeance avails itself to as many and various weapons as it does human motives, while peace is only actualized by a single great one. That is probably peace’s weakness, though an unsurprising weakness when it is dependent upon a manufactured object of devotion.

This piece was intended as a revision of an essay from issue four of Biopsy. Yet the revision was so total from top to bottom that it created a new piece making use of only a few sentences of the old. In fact if you set them side by side they will appear to have been written by two different people. Ironic given the core theme of the essay you are now reading.